BOOKS \ The body reframed

- Liesbeth Aerts

- Dec 12, 2025

- 3 min read

A fresh look at an old fascination

From the moment humans could draw, we’ve turned to our own bodies for inspiration. Painted on cave walls or splayed open in Renaissance anatomical studies, the human body has always been a subject of awe, fear, reverence, and inquiry. What changes across time is how we look at it. Recent books by Ruben Verwaal and Babette Van Rafelghem continue this long lineage in surprising, creative formats, each reframing the body not only as a biological entity, but as a cultural canvas.

At the intersection of science and storytelling, these works echo centuries of bodily exploration through myths, medicine, rituals, and art. Formats evolve, but the question remains roughly the same: what does it mean to know a body?

Fluid histories

In Bloed, zweet en tranen, science historian Ruben Verwaal dives deep into a part of the human body most often left unsaid: its fluids. The original Dutch edition was published in 2023. An English version, Blood, Sweat and Tears: A History of Bodily Fluids, is due in 2026 with August Books.

Verwaal takes what we usually hide—snot, sweat, semen, earwax—and puts it center stage, tracing not just their biology, but the meaning we’ve attached to bodily leakage over time. Why was menstrual blood once believed to curdle mayonnaise? What makes a lover’s saliva soothing, but a stranger’s revolting? How did barbers once double as bloodletting surgeons?

By threading medical anecdotes with cultural oddities, Verwaal builds a fluid history (pun intended) that’s as much about belief and ritual as about biology. Much like our views on hygiene or gender, our ideas about bodily fluids are not fixed. They’re filtered through time, class, culture, and context.

Drawing the dead

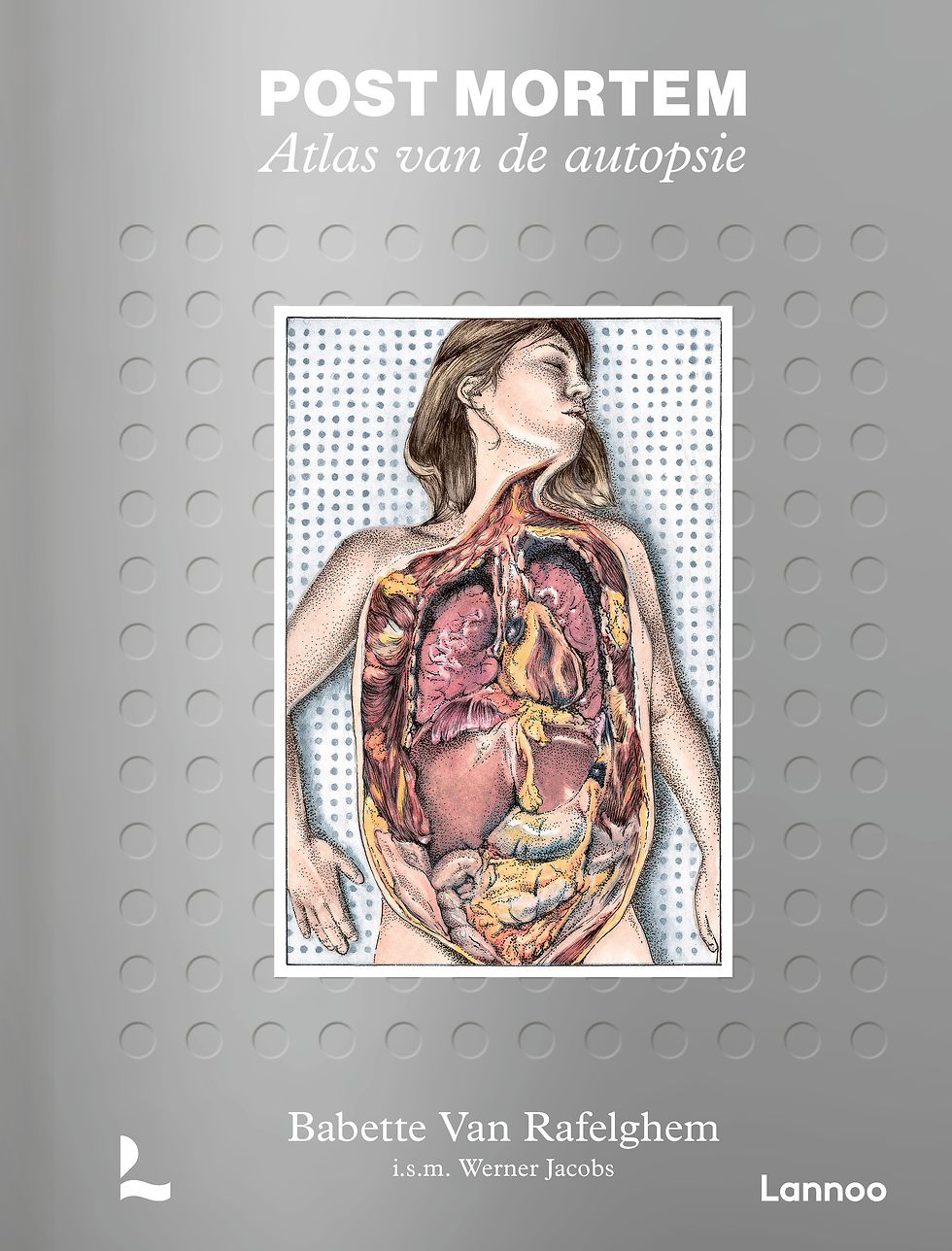

If Verwaal tells the story of what comes out of us, forensic pathologist Babette Van Rafelghem shows what lies within. Post Mortem: Atlas van de autopsie is a book that’s hard to pin down. It’s part art book, part forensic manual, and part memento mori. In stunning hand-drawn illustrations, Van Rafelghem documents the procedure of a full autopsy, inviting readers to look over her shoulder as she uncovers the truth behind suspicious deaths.

Each page reveals a step in the dissection process, rendered not in clinical detachment but with aesthetic care and visual flair. There’s something deeply human about this visual approach. As the body is peeled back layer by layer, we’re reminded not only of our mortality, but also of the extraordinary architecture that holds us together.

The format, an illustrated “atlas,” places Van Rafelghem in the company of figures like Vesalius or Brödel, whose detailed drawings shaped both science and culture. But what makes Post Mortem so contemporary is how it sits comfortably between disciplines: true crime, visual art, medical education, and public engagement.

The art of seeing

These two books speak to a broader trend: science communicators rethinking how we present and perceive the body. From full-color atlases to poetic prose, from Instagram posts to podcasts, new formats emerge not because the subject or the facts change, but because our audiences, our platforms, and our curiosities do.

We’ve seen this before. In the 16th century, Andreas Vesalius fused medicine with performance, staging public dissections as theatrical events. Anatomical wax museums like La Specola in 18th-century Florence turned human dissection into both spectacle and education, with its eerily lifelike models still drawing crowds today. In the 19th century, Ernst Haeckel’s Kunstformen der Natur transformed single-celled sea creatures into mesmerizing, symmetrical works of art. His scientific illustrations inspired not just biologists, but also Art Nouveau architects and chandelier designers. Around the same time, Ramón y Cajal opened up the microscopic universe of the nervous system, using staining techniques and intricate drawings to render the brain’s architecture.

Today, the tradition continues. Luk Cox and Idoya Lahortiga from Belgium-based Somersault (featured in Big Bang edition #2) turn DNA strands, organs, and bones into finely crafted jewelry. They create objects that can be worn, gifted, or cherished as markers of meaning, memory, or even healing.

In its own way, Verwaal’s book uses wit and witless fluids to open cultural conversations. Van Rafelghem’s work transforms death into anatomy-as-art. Both remind us that curiosity about the body is eternal, but the ways we express it are anything but static.

Comments